- Telcos have moved quickly from ‘cloud fear’ to full embrace

- A slew of cooperation agreements has set the scene for more openness and collaboration at the edge

- Exclusivity doesn’t appear to be an option in the telco/hyperscaler relationship scene

The apparent rivalry between telcos and hyperscalers appears to have dissipated and has been replaced by a seemingly endless stream of deals as many traditional network operators have been striking partnerships with the likes of Amazon Web Services (AWS), Microsoft Azure and Google Cloud to assist in the journey to their next generation ‘telco cloud’ platforms and operations, with BT and bell Canada being just two of the most recent examples. (See BT embraces ‘The Digital Way’ with Google Cloud and Bell and Amazon Web Services bring 5G Edge Compute to Canada.)

These partnerships are very often linked to ongoing 5G strategies, with operators seeking the best ways to embrace cloud-native processes such as Continuous Integration/Continuous Deployment (CI/CD) and make use of containerized applications, and the best (perhaps the only feasible) way to achieve those goals in a timely manner has been to tap the hyperscalers, which spent the pandemic years pumping up their abilities to host telcos’ network functions (wireless and fixed) and had been assembling them into branded telecom infrastructures.

As a result, we now have the likes of Microsoft's Azure for Operators and Google's Anthos for Telecom, while AWS has armed itself with a range of technologies and alliances to make itself attractive to telco partners to the point where some see it as dangerously close to having a dominant position.

Previously, some in the telecom industry were wary of consorting with the ‘hyperscale cloud providers,’ fearing they would end up in thrall to a new set of technology jailers, just as they were expecting the technology to be disaggregated and the grip of the two remaining global telecom vendors – Ericsson and Nokia – to be loosened. Huawei, of course, is increasingly missing in action as far as Europe and the US is concerned, while other potentially big players aiming to assist with the telco cloud journey, such as NEC and Samsung, are keen to make up the numbers.

It’s important to note here that some cloud customers, including telco cloud customers, are not averse to a bit of lock-in, since it can make the provider more responsible for performance and problem solving and remove procurement risk, akin to the “nobody was ever fired for buying IBM” scenario. The resulting realisation for telcos was that they needed to buddy up with a cloud player (preferably one of the big three) or even leap into bed with one (as had AT&T with Azure).

Allied to this realisation was the dampening of ‘cloud fear,’ as telcos concluded that hyperscalers were unlikely to become dominant players to their detriment in the way that might have been expected in the past when a Microsoft or an IBM could use their proprietary technologies to stifle competition and fight off antitrust actions in the courts.

The ‘open’ nature of today’s technology makes that outcome less likely and would anyway be squashed by both governments and telcos themselves if it looked like making a return. Cloud is just too important to let it be dominated by a small huddle of tech giants.

The expectation now is that the technology and the likely shape of the business models to emerge will favour multiple relationships across the various technical, geopolitical, regional and business divides. Besides, there are so many options and virtualization approaches now that it’s difficult to see why any one of them might dominate in the long run, plus there are multiple ways that data and apps can move about, with few barriers to a telco using several cloud and hyper-cloud providers for reasons of reach, specialisation, public policy/data sovereignty and, of course, to discipline partners/suppliers. Seeing the cloud market as a carve-up between three US giants is far too reductive… it just won’t happen.

So where are we?

Nobody is sure. Despite all the optimistic projections, the fact is that ’the edge,’ which telcos are setting much store by to grab a piece of the cloud action, is still very much a work in progress, while the equally crucial AI-driven ‘slicing’ technology and standards, which are expected to generate 5G application uptake amongst corporates, is proving very slow to come through with meaningful revenue, or to come through at all.

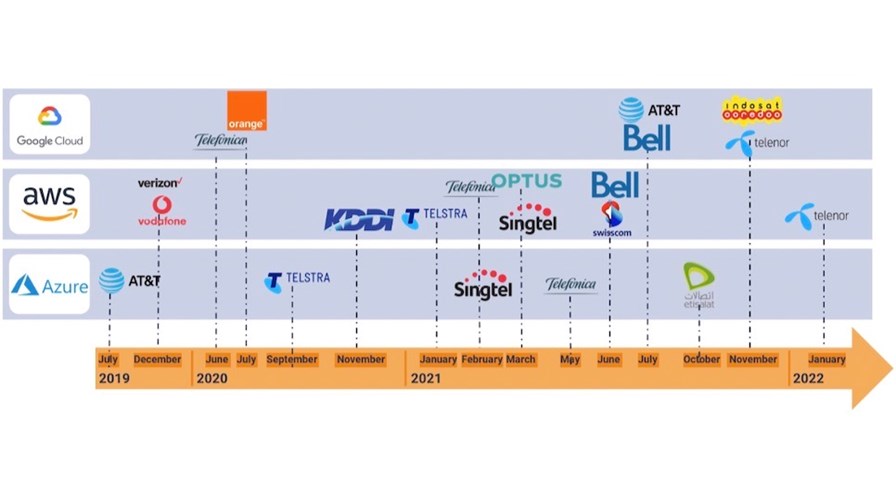

That leaves all sides agreeing technology relationships/agreements to best capitalise on new services and business models as the possibilities become clearer. Hence there has been a spate of agreements involving all the hyperscale players and many of the influential telcos, often with specific reference to ‘the edge.’

Meanwhile – just as a reminder to factor in the hype – important chunks of industry growth appear to be staying on their existing trajectories without making allowances for expected shifts. Take hyperscale data centres: They were supposed to attenuate once the spotlight moved to the edge, resulting in an expanding number of smaller edge data centres to tip the balance from the mega to the smaller. On the contrary, ‘hyperscale’ expansion is now projected to accelerate. According to Synergy Research Group, hyperscale data centres are set to number more than 1,000 globally within three years (there are currently 728) and keep right on growing, hitting 1,200 by the end of 2026. It’s possible, of course, that hyperscale growth will continue and will prompt even more edge growth as it does so. (See How many hyperscale data centres does the world need? Hundreds more, it seems.)

Two-way relationships

London-based consultancy STL, which has been researching the cloud and edge markets from a telco perspective, sees the emerging edge sector as a major telco opportunity, but not simply to act as a vehicle to help hyperscalers reach the verticals they are after.

According to David Martin, Associate Senior Analyst at STL, the most interesting thing from a telco point of view is not the connectivity services they may be able to sell to the hyperscalers, but the technical and other assistance the hyperscalers will be able to offer the telcos in the development of their own services. “MEC partnerships involve a two-way complex relationship,” he says, pointing out that some of the components in a service might be furnished by either party.

As a case in point, BT is rolling out what it calls its ‘Network Cloud,’ supporting its own cloud native solutions for hosting key network functions, such as the 5G core.

“I think this will sit alongside solutions from some of the hyperscalers,” says BT Group’s Chief Technology Officer, Howard Watson. “It’s quite critical that we’re able to deliver low latency services to customers and to allow developers from, say, the AWS ecosystem to be able to write applications to use that low latency,” he said. The recent cooperation agreements often involve explicit references to co-development of edge applications and the two-way nature of the relationships is clear.

Cooperation heats up: Agreements struck between hyperscalers and telcos since January 2019

[Image source: STL Partners - see an extract of the STL Partners report, VNFs on public cloud: Opportunity, not threat]

The move that catalysed the latest rash of cooperation agreements was arguably that signed by Microsoft and AT&T in July 2021. Under that deal, AT&T’s core 5G functions were taken over by Microsoft and managed for AT&T by Azure. Previously, from 2019, both parties co-developed edge compute applications and an edge compute stack that was made available to other telcos as Azure Edge Zones in March 2020

AT&T wasn’t putting all its relationship eggs in one basket though. It worked with Google Cloud from July 2021 to co-develop applications for AT&T’s own MEC platform and network edge capabilities. The interesting thing about this move was the indication it offered of just how diverse and non-exclusive the partnership scene in cloud edge was likely to be. STL makes the point that the partnership with Google seemed unaffected by AT&T’s transfer of its network Cloud to Microsoft, further underscoring the fact that AT&T had retained control over its network functions despite the Azure deal.

Bell Canada first announced an agreement to deploy AWS’s Wavelength in June 2021: The set-up brings AWS compute and storage services to the edge of a telco network where customers can get at them more easily, and that. relationship has just resulted in a deployment in Toronto. And in July 2021, the Canadian telco inked a ‘loose’ deal with Google Cloud to co-develop compute applications over the following decade.

The edge deal flow from 2020 is a bit of a mixture (this is not the full list, just a taster). On the one hand, many telcos are clearly signing limited deals to test the water - a completely reasonable thing to do at this stage of edge development. On the other hand, there is scope for making a bold move that sets the industry back on its heels. The deal signed between AT&T and Azure was certainly that: it reinforced the impression that AT&T was determined to be a bold leader in the telco cloud world (and help put the disastrous foray into content behind it).

Picking winners?

So, which of the hyperscalers will be best placed to support telcos in their effort to cloudify their infrastructure? It’s here that things tend to get a little… err, cloudy. Determining which is the biggest is still probably a good start, but even on this measure punches are pulled.

According to Flexera’s 2022 ‘State of the Cloud’ report, in terms of total spend, AWS is the market share leader in the public cloud, followed by Microsoft and Google, with Azure gaining ground on AWS, while Google is currently “being experimented on by many for potential future plans”: Like a Grade 1 term report, each child gets a mention and a boost.

But Flexera has a point with its reluctance to call out winners and losers at this stage. It affirms that the three front-runners are each spending billions annually on building and equipping new data centers to meet the skyrocketing demand, with Gartner predicting that public cloud services revenue will increase 22% globally in 2022 due to broad acceleration of cloud adoption.

In line with their public cloud growth, all three hyperscalers are keeping up a regular drumbeat of announcements about, and additions to, their telco cloud offerings via the public cloud. (See Azure builds on AT&T’s Network Cloud, offers 5G Core solutions.)

At first thought, the idea of evaluating cloud providers might involve kicking their technology tyres and initiating some sort of benchmark set to see which provider is performing best. Clearly this approach doesn’t really work with the cloud and, in any case, the most important partners may not be infrastructure owners at all. What matters is not today’s performance, but the ability of a provider to stay with the pace and innovate, with alliances playing a big role.

And ‘performance’ is a moving target. Service providers are looking to adopt ‘declarative, intent-based automation,’ which is a completely different way of assuring network performance by using big dollops of AI. With an automated intent model, operators specify their intention for a network configuration, and allow the automated system to meet the intent. A classic case might involve making route choices based on cost against a latency ‘budget’ across the links involved. Since the intention does not change, even if faults occur and networks grow, there is no need to be continually fiddling with route tables: The automation engine evaluates the current state, compares it to the intended state, and takes the actions needed to reconcile the two.

The hyperscalers and their public cloud offerings may be front runners to support the telco cloud, but there are other entities coming up on the rail, many taking a ‘horizontal’ approach to the telco cloud - these include Red Hat and VMware and different approaches to serving corporates which may not rely on the cloud at all. The next article in this series will look at Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) and why it might be a nice fit for telcos.

Email Newsletters

Sign up to receive TelecomTV's top news and videos, plus exclusive subscriber-only content direct to your inbox.